In December, our group of 16 University of Michigan graduate students had the honor of attending the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP) in Dubai, UAE, the meeting of the supreme decision-making body of United Nations Climate Change (the UNFCCC). As students, attending COP 28 presented an opportunity to be involved in the process as arbiters of political transparency – we were there to serve as “observers” to the official negotiations. We would attend negotiation proceedings to ensure visibility and also participate in the larger knowledge sharing and community building that was to occur at the conference. As a community organizer in Michigan, I felt deeply honored to be involved in the process and eager to participate in public engagement on a global scale.

This task was set against an unusually lavish, and somewhat ironic, backdrop in the United Arab Emirates, an oil-rich country that had selected their Minister of Industry and Technology, and the CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, as the President of the COP 28 conference. In our first days at the conference, we wandered the impressively built conference center, taking in the scores of people and events, extravagant museums, art displays, and architecture on the property while listening to the soundtrack of ambient music and fake bird sounds that blasted over conference speakers. The form of the chosen venue and the messages it implicitly, and explicitly, conveyed, however artificial, were expertly designed to instill in attendees a sense of purpose, awe, and inspiration.

With these ironies in place, this conference was being hailed as one of the most important dialogues in climate history, as the United Nations was to assess the outcomes of the first “global stocktake” (GST) of the Paris Agreement. The GST sought to assess the progress made towards meeting the global climate goals and to inform how governments could change course if those goals were not met. The assessment conducted last year illustrated the massive gap in emissions reductions, with current national commitments falling short by 20.3 to 23.9 gigatons of CO2 equivalent compared to the levels required to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030. More specifically, and of key importance to the negotiators present at COP 28, this revelation meant that to achieve the Paris Agreement’s targets, global greenhouse gas emissions need to be cut by around 43% by 2030 and 60% by 2035, aiming for net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

This dire reality framed the 2023 negotiations and the character of the conference. On the surface, COP 28’s public messaging mirrored this. During our time at the conference, we had the opportunity to explore both the private zone, where the negotiations took place, and the public zone, which was focused on information sharing and public education. Both zones were teeming with reminders of the scope of the threat of climate change on world communities.

The conference center housed hundreds of pavilions dedicated to the exchange of information and knowledge by climate experts from across the globe. In this way, COP 28 not only served as a venue for the negotiations themselves, but for collaboration across all sectors and all countries on forward progress. Especially in the public zones, the design of the conference was primed to amplify this message. Around every corner, there were gathering spaces for attendees to share their experience and to connect. The schedules were packed with large events, both public and private, to discuss cutting edge climate science, sustainability techniques, and innovation. There were hubs for green startups to display their technologies, an urban farm located on the venue, and reminders on every sign and on every food booth that the cutlery that was passed around the center was compostable.

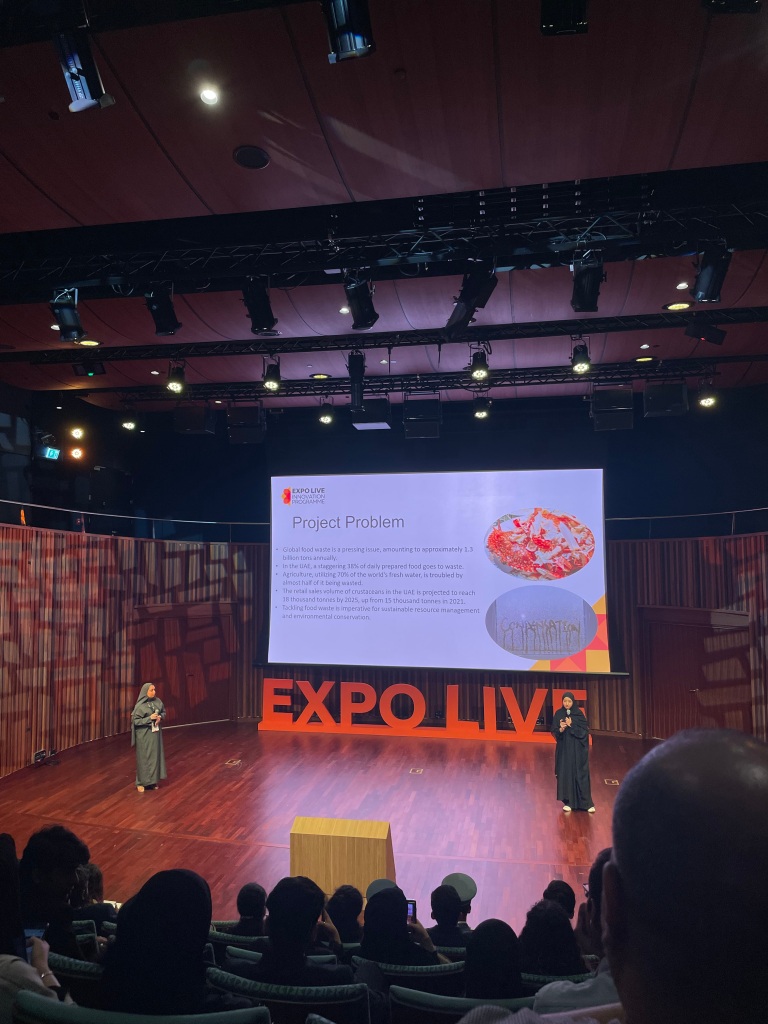

Staggeringly, the center was also filled with immersive museums, some focused on the contributions of the UAE to sustainability, some on the acute danger of climate change, and some on the potential of human connectivity and innovation. In between talks, we walked between these museums, often surrounded by hundreds of children who had come to see the conference center in their school groups. Throughout my COP 28 experience, I was most moved and inspired by a competition event called “Expo Live”, held by the UAE government, that encouraged university students to compete for a government grant to fund their innovative local sustainability solutions. Largely, the organizers of COP 28 had presented and packaged the conference not only as a venue for the official United Nations negotiations, but as an opportunity to educate the public about the potential of global sustainability efforts.

This messaging was, at first, inspiring. It led me to feel immersed in a center of climate innovation and made me hopeful of the potential for innovative and aggressive action. At the same time, the negotiations rolled forward with a sufficient agreement seeming further and further away. By now, the outcomes of COP 28 have been discussed, assessed, celebrated, and lamented by many. The conference presented a mixed bag of both forward-thinking policies and disappointing failures of consensus. This COP was the first to officially acknowledge that fossil fuels are the root cause of climate change and to introduce language about the necessity to “transition away” from them as a fuel source. There were also significant contributions to climate financing for developing countries as well as pledges to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030. While these were positive steps in the direction of climate progress, many felt discouraged by the lack of definitive commitments to climate action that, ultimately, make the goal of achieving warming below the 1.5 degree Celsius level extremely challenging to achieve. Without enforceable commitments and a definitive plan to transition away from fossil fuels, many of the goals of the Paris Agreement may become impossible to reach.

As an attendee, this stark difference between COP 28’s public messaging and private failure to legislate on climate issues felt insidious. While they educated the public on why the negotiations and climate action was necessary, the negotiators were not able to reach a consensus on the most important and contentious issues. The conference held stunning potential for meaningful education that coincided with meaningful policy. Instead, the organizers succeeded in putting on a moving show for attendees with their music, bird sounds, compostable cutlery, and museums, while failing to take sufficient action to protect future generations. For future COP conferences, especially for the next conference in Azerbaijan, my hope is that the organizers back their strong public engagement with meaningful policy.