Author: Allison Baumgartner, University of Michigan, School of Public Health

Introduction. Last November, delegations and observers gathered from across the globe to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of Parties (COP) to discuss and reach a consensus on climate change goals and national commitments. As a global health epidemiologist, the second week of COP 29 negotiations and side events provided an eye-opening opportunity to observe the process of international negotiation and nuanced conversations on climate change. While leadership put climate financing as the forefront priority of COP 29, I found the high-level speeches, informal hallway discussions, and intense climate negotiations through the lenses of health and gender equality most interesting. From my perspective, it became clear that the outcomes of COP 29 could profoundly affect the health of billions worldwide.

Finalized COP reports are the ‘shiny end product’ of a complex, challenging (and messy) process. Following years of research and collaboration across multidisciplinary partnerships (including public health), COP decisions emerge from informal conversations, maintenance of diplomatic relationships, and fierce wording/punctuation placement. While global voices often criticize the meager national commitments outlined in finalized conference documents, the consensus reached each year at COPs still provides hope toward more outstanding obligations. As ongoing negotiations are challenged by disparate national ideologies and motivations for committed action, enhanced global awareness of these meetings remains imperative. Collective action only emerges through ongoing dialogue through forums such as COP 29.

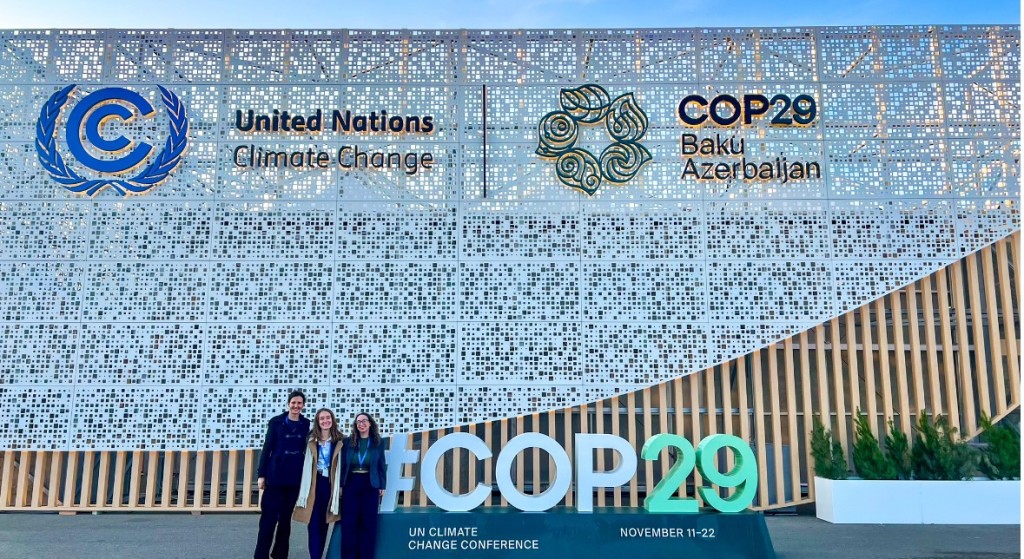

Overview of COP 29. The Conference of Parties (COPs) is an annual meeting established in 1992 through a multilateral treaty by UNFCCC. These gatherings aim to propel global commitments towards emission reduction, climate change adaptation, Loss and Damage financing, and enhancing resilience to climate change crises [1]. Baku, Azerbaijan, was the venue for COP 29, held from November 11 to November 22, 2024. Conference leadership underscored climate financing as a fundamental priority, with participating nations strategically preparing for the upcoming third-round submission of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs 3.0), scheduled for February 2025 [2-3]. Delegates from the Small Island Developing States passionately urged developed nations to step up their commitments to climate financing. As discussions carried on into the early hours of Sunday, November 24, high-emission countries showed hesitance to take on more financial responsibility. This reluctance only intensified the contentious negotiations and led to walkouts. The situation raised serious questions about whether all parties acted in good faith, echoing concerns rooted in Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties [4]. Nonetheless, the parties reached a consensus in Baku, yet the exercise highlighted a stark, cruel paradox. Countries that could make the most significant difference seem the least eager to take on extra financial burdens. At the same time, those who bear the brunt of climate change—the most vulnerable communities—are not only the most vocal advocates for change but also need and require external support: unable to independently adapt to the catastrophic impacts of climate change. This disconnect may stem from climate change feeling abstract to many in developed countries. Take, for instance, the average American—climate risks can seem distant and disconnected from daily life. For wealthier nations, the drive for positive change often relies on a sense of “benevolence,” despite the reality that climate change affects all countries to varying degrees. Conversely, for those grappling with the direct catastrophic impact of climate change, the issue is one of justice. This divide creates a philosophical deadlock and a frustratingly slow pace of progress. Amid whispered conversations on crowded planes and lively exchanges in conference halls, many attendees questioned the relevance of UNFCCC COP summits. As the global landscape shifts, the urgency for collaboration and commitment to tackling climate change has never been more pressing.

The Intersection of Climate Change, Global Health, and Gender Equality. The “One Health” framework underscores the intrinsic connections between communities, animals, and climate health [5]. This approach becomes particularly relevant when considering real-world examples: how air quality directly influences childhood asthma rates or how access to nutritious food plays a crucial role in cardiovascular health [5]. Exposure to environmental toxins can lead to pregnancy complications, while deforestation significantly raises the risk of infectious disease spread from animals to humans, leading to outbreaks [5]. As highlighted by Philip E. Wilson, Jr., the climate crisis is a global issue that knows no borders, embodying the tragedy of the global commons [6]. He argues that we must unite, transcending individual interests, in protecting vital resources like rainforests that require a delicate balance of supply and demand [6]. So, too, global public health.

In public health, we often refer to the climate crisis as a “wicked problem.” This term captures its complexity—an intricate web of challenges leading to various adverse health outcomes that resist positive change due to conflicting social interests. When one community grapples with severe health challenges from climate-induced zoonotic spillovers—where pathogens jump from animals to humans due to habitat destruction—or faces famine stemming from erratic rainfall patterns and extreme weather events, the ripple effects are felt far and wide [5]. However, the impact isn’t equitably distributed; those already vulnerable are pushed further into hardship [7]. Women, children, and older adults often bear the brunt of these climate-induced challenges, facing restrictions on educational and employment opportunities, safety, and overall well-being [7]. Addressing the interconnected health, climate, and inequality challenges requires a united effort to prioritize the most vulnerable.

COP 29 Outcomes. The recent COP 29 negotiations stirred optimism and disappointment among the participating parties, culminating in a significant commitment of $300 billion in annual climate financing by 2035 [8]. While this figure represents a bold leap—three times higher than previous pledges—developing nations and Small Island Developing States expressed dissatisfaction with what they still perceive as a ‘low’ commitment [8]. To put this into perspective, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the global community mobilized a staggering $17 trillion through fiscal measures from January 2020 to September 2021, with G-20 economies contributing a massive $15.3 trillion [9-10]. The significant response to the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the potential for collective action when confronting existential threats. Given the remarkable financial mobilization by the global community during this crisis, it is understandable that developing countries feel disheartened by the relatively modest financial commitments made at COP 29.

Yet, amidst the challenges, glimmers of hope emerged from discussions around health and gender equality [8]. Extending the Lima Work Programme on Gender and Climate Change for another ten years signals a sustained global commitment to integrating gender considerations into climate discussions [8]. Additionally, key leaders from nations including Nigeria, Fiji, Jordan, Mozambique, the Netherlands, and Germany—alongside prominent organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO), Lancet Countdown, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—came together to emphasize the vital intersection of climate and health during COP’s second annual ‘Health Day’ [8]. This high-level roundtable solidified commitments by signing a Letter of Intent, establishing the Baku COP Presidencies Continuity Coalition for Climate and Health, spearheaded by Azerbaijan, Brazil, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom [8]. The establishment of ‘Health Day’ at COP 28 marked a pivotal moment, fostering meaningful discussions at the UNFCCC COP table about the vital links between health, gender equality, and climate action. By prioritizing these conversations, negotiators are reminded of our shared humanity, paving the way for inclusive policies that safeguard the health and well-being of communities around the globe.

Conclusion. Amid the challenges in negotiations that unfolded in Baku, these talks brought together global players united by the urgent goal of climate action. While aware of each member state’s different agendas, no single nation can tackle the climate crisis alone. Similarly, no country can face the next pandemic or resolve other pressing global issues in isolation. Think of global coordination as a complex but necessary group project. It’s messy and sometimes frustrating, but it thrives on shared commitment—communication, relationship building, and compromise for the greater good. As nations engage and share the realities of climate change in ways that resonate with their people, we recognize the profound implications of our collective actions. Whether we take bold steps toward progress or succumb to inaction, global obligations at COP impact individuals’ lives worldwide, from communities in North Carolina to women in Bangladesh and caregivers in the small island nation of Grenada. COPs serve as essential platforms for amplifying these voices and sharing their stories. While remaining important for quantifying the significant burden of climate change around the globe, we risk losing hope when discussions reduce this crisis to mere statistics or monetary figures. Personal narratives remind us of our shared humanity. Stories help contextualize the situation in terms that we can all understand. As long as leaders worldwide are willing to come together—rolling up their sleeves to collaborate on a future where all communities can thrive, live, grow, pray, and play free from the grips of the climate crisis—there is still hope.

References

- UNFCCC. How COPs are organized – Questions and answers. United Nations Climate Change. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/conferences/the-big-picture/what-are-united-nations-climate-change-conferences/how-cops-are-organized-questions-and-answers

- UNFCCC. About COP 29. United Nations Climate Change. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://unfccc.int/cop29/about-cop29

- United Nations. All About the NDCs. United Nations. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/all-about-ndcs

- United Nations. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. United Nations; 1969:331. https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf

- Mackenzie JS, Jeggo M. The One Health Approach—Why Is It So Important? TropicalMed. 2019;4(2):88. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed4020088

- Clancy EA. The Tragedy of the Global Commons. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies. 1998;5(2). https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol5/iss2/12

- UN Women. How gender inequality and climate change are interconnected. UN Women, For All Women and Girls. April 21, 2025. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.unwomen.org/en/articles/explainer/how-gender-inequality-and-climate-change-are-interconnected

- UNFCCC. COP29 UN Climate Conference Agrees to Triple Finance to Developing Countries, Protecting Lives and Livelihoods. United Nations Climate Change. November 24, 2024. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://unfccc.int/news/cop29-un-climate-conference-agrees-to-triple-finance-to-developing-countries-protecting-lives-and

- Urama KC, Mukasa AN, Simpasa A. Turning Political Ambitions into Concrete Climate Financing Actions for Africa. Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings; 2023:130-134. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/climate-change-adapting-to-a-new-normal/

- Cole J, Dodds K. Unhealthy geopolitics: can the response to COVID-19 reform climate change policy? Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(2):148-154. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.269068