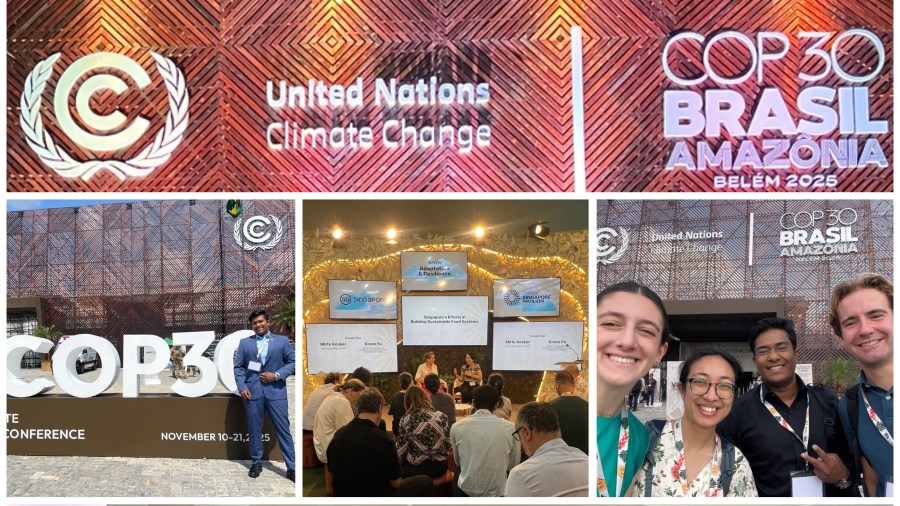

Attending COP30 in Belém was transformative not just because of the negotiations I sat on, but because it fundamentally shifted how I think about the relationship between global climate policy and corporate climate strategy. Coming from a background in sustainability systems, ESG reporting, and decarbonization planning, I found myself constantly linking what was happening in the negotiation rooms to the everyday challenges businesses face when trying to take climate action seriously.

When Policy Uncertainty Meets Business Reality

Walking into an Article 6 negotiation for the first time, I immediately realized how deeply corporate climate action depends on what is decided in these rooms. A single word welcome vs note, request vs urge can ripple across carbon markets, investor confidence, and national implementation strategies.

One of the most striking sessions was the debate on how to allocate residual Article 6 funds. Countries disagreed on percentages, on whether the money should explicitly mention response measures, and even on which trust fund it should land in to avoid political signaling. What struck me was how closely this mirrored corporate sustainability decisions:

- How do you allocate limited climate dollars?

- How do you balance short-term mitigation needs with long-term resilience?

- How do you maintain transparency without over-exposing vulnerabilities?

The tension between precision and flexibility is something corporates navigate every day.

Business Needs Clarity to Act Not Ambiguity:

Throughout the COP, I kept hearing variations of the same concern from delegates: We are now in implementation mode. We need rules we can actually work with. This resonated deeply with what I’ve seen in the corporate world. If policies or methodologies are vague, companies either wait or, worse, act without integrity because guardrails are missing. The debate surrounding the transition of the CDM, and the emotional moment of formally closing it, made me appreciate how much institutional memory matters. The CDM established global standards for baselines and monitoring, and now Article 6 must carry that legacy while ensuring business participation remains credible, not opportunistic.

For businesses, the lesson is clear: High-integrity climate action requires stable, science-based rules.

Where Policy Meets Practice: Transparency, Carbon Markets, and Supply Chains

Some of the most relevant discussions for business came from transparency and reporting sessions. The Biennial Transparency Report (BTR) synthesis work reminded me of the essential role comparable, accessible data plays for both governments and companies. Whether it’s Scope 3 reporting, supply-chain disclosures, or emissions accounting, companies rely on national systems that are built here. When countries debated how to design indicators for the Global Goal on Adaptation, I saw the same struggle that companies face in ESG:

- How do you measure what isn’t yet measurable?

- How do you report what you don’t have data for?

- How do you balance precision with the burden of reporting?

Similarly, the session on responsible mineral supply chains (EITI, ICMM) reinforced the massive governance gaps in the transition-minerals economy. As someone interested in sustainable industries and business leadership, I found it encouraging that transparency, traceability, and community rights are becoming central to the business conversation not afterthoughts.

Private Sector Solutions Were Everywhere

What truly inspired me was seeing how business innovation is already driving solutions, even where policy is still catching up. At the water circularity session, companies such as Novonortis, Heineken, and PepsiCo demonstrated closed-loop water reuse models that save 18 million litres per month, scaling to 1 billion litres over five years. The message was simple but profound:

“Waste is the villain, efficiency is the hero.”

I saw this again at the Indonesian Pavilion’s geothermal discussion, Japan’s carbon capture and moisture-efficient cooling demonstrations, and corporate dialogues on aligning NDCs with business action. Across these examples, one thing was clear: Businesses are ready to lead when the rules enable it.

A Personal Reflection: Why a Business Lens Belongs at the COP

As I sat between negotiators from LMDC, AOSIS, the EU, and the African Group debating commas and words in Article 6 text, I realised that this is exactly where the corporate community needs to be paying attention. The frameworks built here aren’t abstract; they shape investment decisions, supply chains, financing flows, and the credibility of every net-zero claim made in a boardroom. My biggest takeaway from COP30 is that Climate policy and business strategy can no longer operate as separate entities. Implementation requires both to move together. For me, as someone committed to working at this intersection, whether through carbon markets, ESG strategy, or sustainability innovation, COP30 was the clearest reminder that real climate action will occur only when the private sector and global governance reinforce, rather than contradict, each other.

And as we move toward COP31, the question isn’t just what will countries agree to next? The question is:

How will businesses rise to meet the clarity, responsibility, and ambition that the Paris Agreement now demands?